Alvin C. Hollingsworth – the Don Quixote Series

Created by Patricia A. Hobbs

Created by Patricia A. Hobbs, Associate Director and Curator of Art and History, University Collections of Art & History, Washington and Lee University. Thanks also to Brittany Lloyd, WL’15, for initial research assistance.

This lesson can be used or adapted by other educators for educational purposes with attribution to Hobbs. None of this material may be used for commercial purposes. Copyright of original artworks belongs to the artist. Reproduced with permission from the artist. Please contact Andrea Lepage for information the Teaching with UCAH Project: lepagea@wlu.edu or (540) 458-8305. Toolkit Lesson for Alvin Hollinsgworth by Patricia Hobbs is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“The most important facet of an artist’s work is his individual approach to his subject matter. It does not matter whether he is a commercial artist or a fine artist; it is his unique abilities and style that will bring him recognition.”

-Alvin C. Hollingsworth, “Teaching Art to the Gifted in a New York High School.” American Artist, June 1964

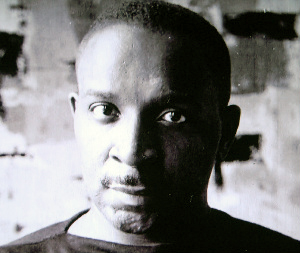

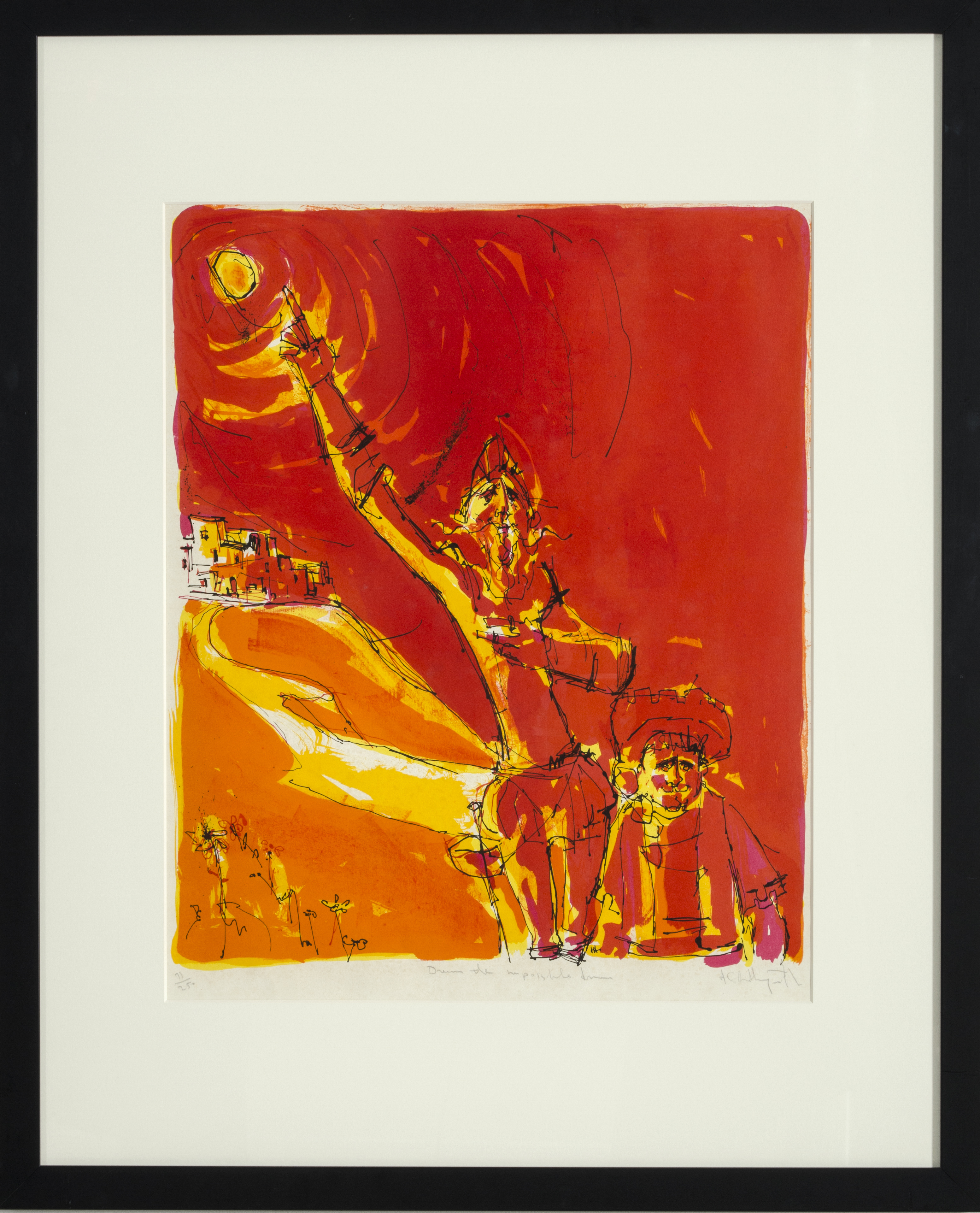

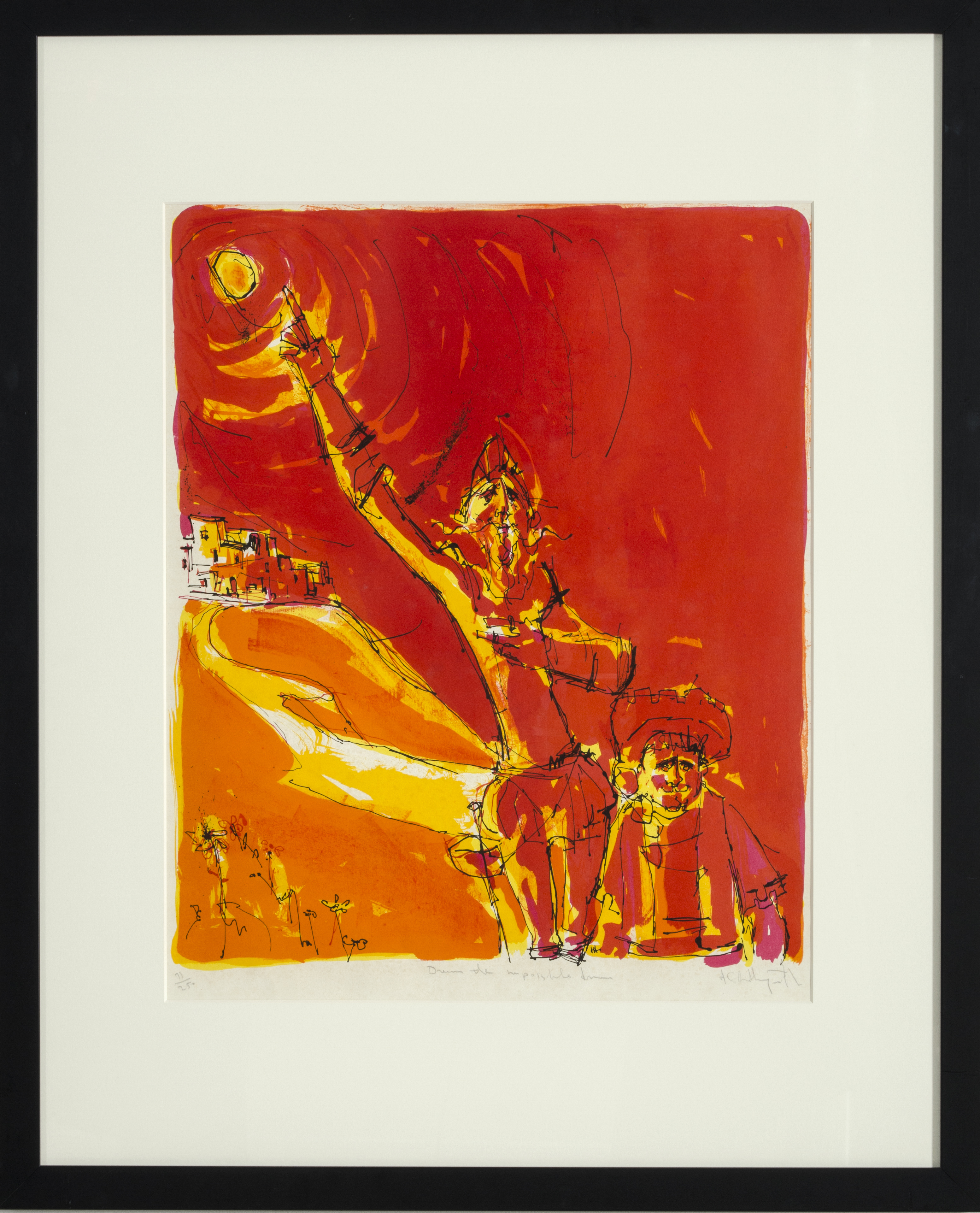

Alvin Carl Hollingsworth (1928-2000) was a leading African-American artist and educator, who began his career as a comic book illustrator. He is notable for being a member of the Spiral Group, a coalition of black artists brought together by Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis in response to the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom planned for August 1963. In the 1970s, Hollingsworth painted wall murals for the Don Quixote Apartment Building in the Bronx, NYC. About the same time, he created a series of lithographs and paintings depicting the characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Washington and Lee University owns three of the 13 different print editions that have been identified thus far using the theme of Don Quixote.

The objective of this toolkit is to demonstrate how visual analysis of these Don Quixote prints – when considered in light of Hollingsworth’s biography and supporting documentation – can serve as vehicles of learning for a variety of disciplines, including world literature, musical theater / film, post-1945 art and popular culture, the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, and African-American Studies, among others. The five sections include:

- The Iconic Don Quixote in Literature and Pop Culture

- Alvin Carl Hollingsworth: Rooted in Harlem

- C. Hollingsworth (AKA Alvin Holly): Comic Book Illustrator

- Al Hollingsworth, the Spiral Group, and the 1960s Civil Rights Movement

- Al Hollingsworth and Don Quixote / Man of La Mancha: Reflections of an Era

See also:

- Selected bibliography for further reading

- Exercises and Activities for further discussion:

- The Iconic Don Quixote in Literature and Pop Culture

- Alvin Carl Hollingsworth: Rooted in Harlem

- A.C. Hollingsworth (AKA Alvin Holly): Comic Book Illustrator

- Al Hollingsworth, the Spiral Group, and the 1960s Civil Right Movement

- Al Hollingsworth and Don Quixote / Man of La Mancha: Reflections of an Era

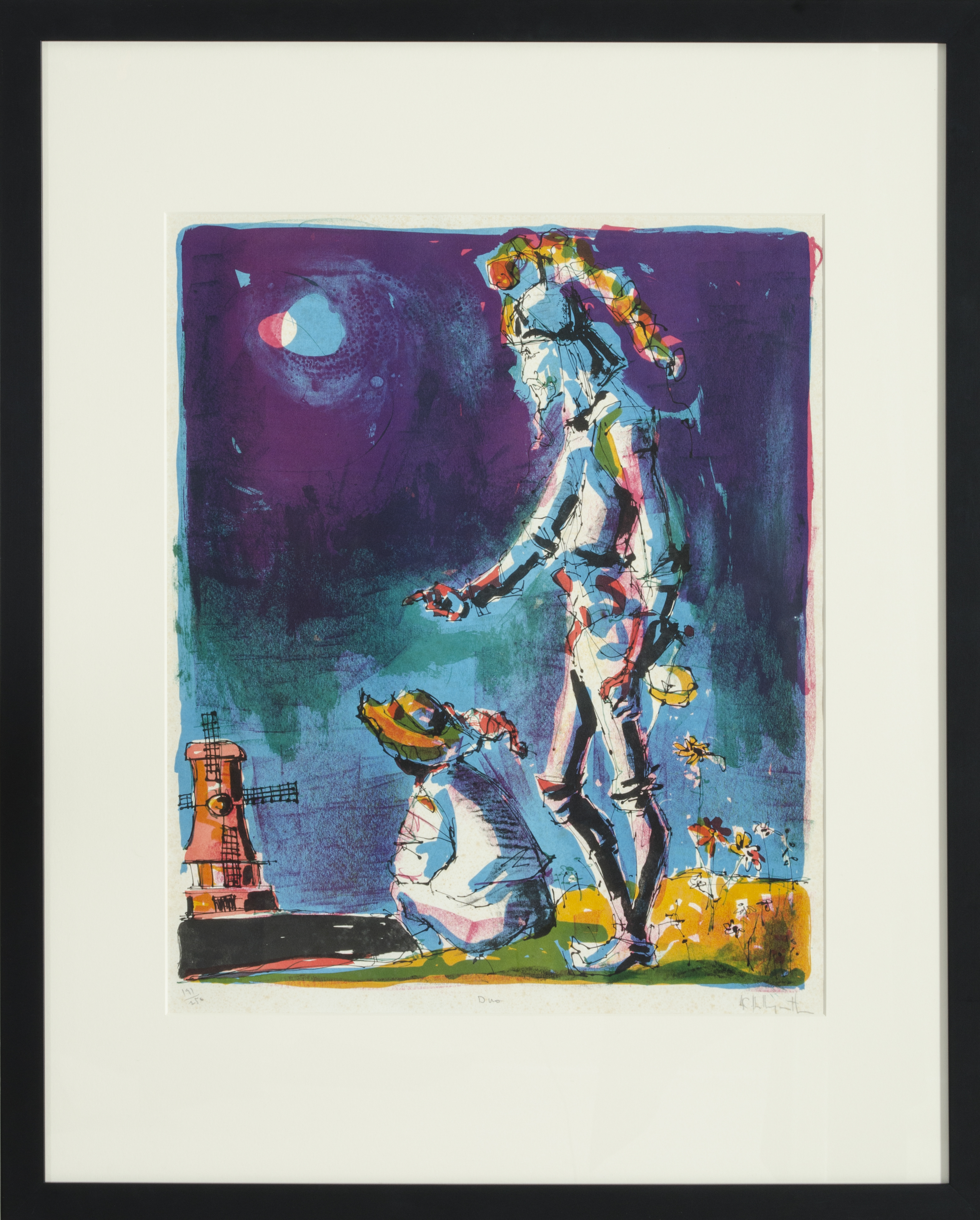

Alvin Carl Hollingsworth: Don Quixote Series, ca. 1979 Left to right: Duo; Attack at Dawn; Dream the Impossible Dream. Lithographs, editions of 250. University Collections of Art & History, U2006.0.32-34

________________________________

The Iconic Don Quixote in Literature and Pop Culture

When studying the major work Don Quixote by Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616), Hollingsworth’s prints offer additional means for students to explore the iconic characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Close examination of the lithograph entitled “Duo” opens possibilities for in-depth consideration of the illustrated characters and their comparison to Cervantes’ literary descriptions. Additionally, the print “Attack at Dawn” provides the opportunity to discuss through the eyes of an artist the first of the pair’s chivalric misadventures – the famous episode of the tilting at windmills.

The literary work has provided inspiration to many artists besides Alvin Hollingsworth, including Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dali. It is interesting to compare the variety of depictions. At the same time, art has influenced the interpretation of Cervantes’ work as well. In her blog post “Picturing Don Quixote,” Rachel Schmidt, professor of Spanish at the University of Calgary, explores how the varying approaches to illustrating the tale have reflected and impacted its reading through the centuries.

As one of the world’s most influential works of literature, Cervantes’ book, its characters and their actions have become recognizable elements of popular culture. Hollingsworth’s third print “Dream the Impossible Dream” actually references a modern mid-20th century interpretation of Cervantes’ work, the musical Man of La Mancha by Dale Wasserman. “The Impossible Dream (The Quest)” by Mitch Leigh with lyrics by Joe Darion was the principle song in both the musical and a later film version by the same name. The song became a popular music standard almost immediately, reaching No. 1 in 1966, and has been recorded multiple times since its debut.

Man of La Mancha, a comic tragedy, was a 1964 adaptation by Wasserman of his 1959 play for television entitled I, Don Quixote. It is not a retelling of Cervantes’ book, but relates the story of Cervantes, a tax collector and author jailed and awaiting trial by the Spanish Inquisition, who attempts to save the manuscript of his novel Don Quixote from confiscation by his fellow prisoners. He offers a defense in the form of a play, performed by Cervantes and his servant Sancho, with help from the other prisoners. Moved by his story, they return his manuscript just as Cervantes is summoned to his real trial.

The theme of the Tony award-winning musical reflected the idealism of the tumultuous decade of the sixties that included the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the Vietnam War, and a search for social justice. The musical, which continues to be staged, has been revived on Broadway multiple times, the last in 2002, and its 50th anniversary was commemorated by many theaters in 2015. In 1972 it was adapted into a film by the same name, starring Peter O’Toole and Sophia Loren, which boosted its popularity even further.

For video of the original Broadway musical cast seen in 1965 on The Ed Sullivan Show, and for an excerpt from the 1972 film, click here and here.

________________________________

Alvin Carl Hollingsworth: Rooted in Harlem

Hollingsworth’s parents were emigrants from Barbados who married and settled in the Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem in the early 1920s. Alvin was born in 1928, just a year before the stock market crash that led to the Great Depression, when jobs became scarce and unemployment soared. But Harlem was also the center of the “flowering” of African-American culture that took place between the end of WWI and the mid-1930s. Known as the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic, literary and intellectual movement was transformational and kindled a new black identity and cultural pride, in spite of rampant racism and few economic opportunities. This was the crucible in which Hollingsworth was raised

“Harlem was a thriving community which pulsated with life, a convergence of sight, sound and color, and a pivot for people of color. A community which supported art created within its confines, jazz, poetry, murals, sculpture, and paintings. This was the world Alvin grew up in.”

-Valliere Richard Auzenne, Hollingsworth biographer, Quoted in Ink-Slinger Profiles: A. C. Hollingsworth

Left: Taxis line up outside of the Cotton Club at Broadway and 48th Street, ca. 1938. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.

Right: Harlem Street Scene, n.d, U.S. National Archives

Blacks continued to pour into Harlem from points in lower Manhattan, the American South and the Caribbean. With the onset of the First World War in 1915, many foreign immigrants set sail for their homelands, leaving employment opportunities available in the war industries in the north. Blacks migrated in record numbers from the south to northern cities in search of opportunities and increased wages.

During the 1920’s, Harlem flourished with cultural and artistic expression. This period was christened the “Harlem Renaissance”. Harlem Renaissance figures such as Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Alain Locke and others felt that they would use their artistic creativity as a means to show America and the world that Blacks are intellectual, artistic and humane and should be treated accordingly.

The Great Depression of 1929 rocked the country and devastated Black communities such as Harlem. The pressure of high rents, unemployment and racist practices cumulated in Harlem riots in 1935 and 1943. The Second World War offered Blacks few opportunities for advancement, and Blacks mobilized against the war industry demanding fair practices. Militant activities during the 1940’s set the stage for the 1960’s.

Harlem was both stage and player during the turbulent period of the Civil Rights Movement. Religious and political leaders articulated the sentiments of the masses from street corners and pulpits throughout the community. During the 1960’s, figures like Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Queen Mother Moore and Preston Wilcox used Harlem as a launch pad for political, social, and economic empowerment activities. Social problems caused a decrease in Harlem’s population during the late 1960’s through the 1970’s, leaving behind a high concentration of underprivileged residents and a fast decaying housing stock.

-From: History of Harlem

________________________________

A.C. Hollingsworth (AKA Alvin Holly): Comic Book Illustrator

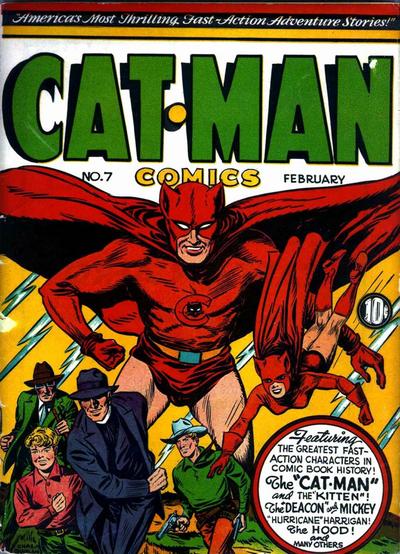

One of the first African American comic book illustrators, Hollingsworth grew up during the explosion of comic book publications in the 1930s and early 1940s, known as the Golden Age of Comic Books.

Cover of Superman #1 (Summer, 1939), Art by Joe Shuster, Comics.org.

While the origin of comic books dates to the 19th century, the form flourished in the first half of the twentieth century during a time of immigration, economic depression, and a world war. Most historians agree that the Golden Age of Comic Books began with the 1938 publication of Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Its success led to series of increasing numbers of superheroes, including Captain Marvel, Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, and Green Lantern.

The reason for Superman’s instant popularity in the late 1930s is obvious: during this time, America was a nation of immigrants. People were coming from all over the world in search of “The American Dream.” Superman, as the last survivor of the doomed planet Krypton, is the ultimate immigrant. It wasn’t uncommon for children to be separated from their parents during this time, either in their home country or once they got to Ellis Island. This is the feeling, of both adventure and uncertainty that Siegel and Shuster, both the sons of European immigrants, tapped into with their strange visitor from another planet.

https://www1.heritagestatic.com/comics/d/history-of-comics.pdf

The comic book industry flourished during World War II, when inexpensive, patriotic tales in which good triumphed over evil were published. Captain America was a key character, assisting the U.S. war effort in its fight against Adolph Hitler. In addition to the superhero comics, horror and crime series were also popular during the Golden Age. New styles continued to develop, including young romance and science fiction, among others. After the war, the sale of comic books waned for some time, but the comic strip and comic book had already become a mainstream art form, with its own defined language and creative conventions.[i] Even now, after all these years, Superman remains one of popular culture’s most lasting superheroes.

As older experienced artists left to serve during the war, young talented teenage artists were in demand for their artistic skills by the publishing houses and newspapers that hired and trained them.[ii] As a young boy, Hollingsworth drew cartoons of superheroes leaping from the Empire State Building. By the age of 14, he was working as an artist assistant at Holyoke Publishing Company, running errands and doing paste-ups and touchups for comic books, including Cat-Man. Because of the connections he made at Holyoke, he was introduced to and ultimately attended the High School of Music and Art in New York City, founded in 1936.[iii]

“My first cartoons were city scenes picturing the Empire State Building, cartoons where superheroes would be leaping from building to building. I got my first job [in comics] while I was in junior high school.”

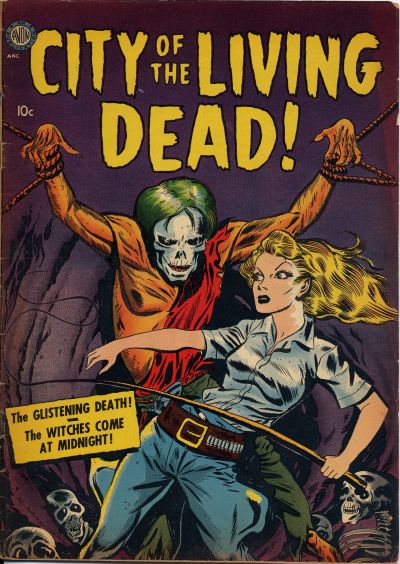

During high school, Hollingsworth became a comic strip illustrator under his own name as well as under various pseudonyms, including “Alvin Holly.” He worked within several genres, including superheroes (such as Holyoke Publishing’s Cat-Man Comics in the early 1940s), crime comics (including “The Million Dollar Robbery” in the series “Crime Does Not Pay” #31 published in January 1944), war comics (including “Robot Plane” in Aviation Press’ Contact Comics #5, 1945), horror comics (including “City of the Living Dead” in 1952), and young romance comics (Negro Romance in the 1950s). Not only was Hollingsworth young, but he was also one of the first African-American comic book illustrators in the business.

Contact Comics #5, 1945, Published by Aviation Press, “Robot Plane” comic story, pencils and inks by Alvin Hollingsworth (pencils signed), Comics.org.

City of the Living Dead!, 1952, Cover signed A.C. Hollingsworth (pencils and inks), Published by Avon, Comics.org.

During the 1940s through the mid-1950s, America’s Black press experienced a newspaper comic strip renaissance. For the first time, black newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier published comics that featured African American principle characters drawn by African American artists and provided by cartoon syndicates like Smith-Mann.[iv] Unlike the exaggerated caricatures of blacks found often in mainstream comics, the comic strips of the Black press featured characters rooted in the “thriving Black middle class that prospered under segregated conditions to build financially thriving communities.”[v] Leading artists included Jackie Ormes, the first African American female cartoonist noted for her romance comics featuring protagonist Torchy Brown. In 1954, Al Hollingsworth’s comic strip Kandy replaced Ormes’ Torchy in Heartbeats in the Philadelphia Courier. Published for one year in black and white only, Kandy was “an action-filled tale of competitive auto racing in the shadow of ruthless corporate espionage.”[vi] It featured Kandy MacKay, a young African American woman engineer who designed and built cars, and Rod Stone, a black competitive racecar driver. As Tim Jackson wrote in Pioneering Cartoonists of Color, “The Courier comics show us that people of Color, too, can win the big race while overcoming adversity with self-confidence and bravery, the way auto racer Rod Stone was able to do in Al Hollingsworth’s Kandy comic strip. Kandy also showed young girls it was possible to be a Black and a woman engineer like Kandy, and like Kandy and [her father] Pops MacKay, an African American, start their own businesses as well.”[vii]

Hollingsworth’s comic book work is an example of pop culture, a term defined as “cultural activities or commercial products reflecting, suited to, or aimed at the tastes of the general masses of people.”[viii] The word “comics” refers to a medium that expresses ideas by using deliberately sequenced images arranged to convey information or elicit a response.[ix] These images are not always detailed, but are often simplified and easily identifiable representations. Lines convey information through variations in weight, providing emotional qualities or types of action, and text is often added. Each drawing is contained within a frame and the gutter, the space between the panels, can also imply action of some sort. The images are arranged in parts that the viewer perceives as a whole. Colors, if used, are often flat. Comic books of the 1940s and ‘50s were printed mechanically and published widely, and were an inexpensive, accessible art form for boys of all incomes. One can argue that many elements of Hollingsworth’s early comic book work can be found in his later artwork, including hi Don Quixote series of lithographs.

Hollingsworth graduated from high school in 1946, attended the Art Students League in 1951, and continued to work as a comic book illustrator until 1954, when “he was fired from his cartoon job for demanding more money, and at CCNY he switched from social studies to fine art.”[x] After he graduated in 1956 from the City College of New York (CCNY), Hollingsworth began to exhibit his own artwork, participating in the 45th Annual Newport Art Association Show. He received a master’s degree from City College in 1959, and in 1961 had his first solo exhibition “Exodus” at the Ward Eggleston Gallery, NYC. He was also part of a group exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. By the 1960s, Hollingsworth taught art privately and at the High School of Art and Design while working on a doctorate at the School of Education at New York University. He also worked as a graphic artist and illustrator, and pursued his own work as a fine artist, among many other interests.[xi] Interviewed in American Artist and recipient of the Emily Lowe Award in 1963 as well as the Whitney Foundation award in 1964, Hollingsworth was becoming recognized as a rising black artist with great promise.

________________________________

Al Hollingsworth, the Spiral Group, and the 1960s Civil Right Movement

Identifying himself as a member of the “beat generation,” Hollingsworth became involved with the art and intellectual interests of Greenwich Village in the late 1950s.[xii] He worked on various series of paintings, prints and drawings that included the Beat Scene, incorporated fluorescent paints, and reflected a fascination with the architecture of the Guggenheim Museum, which was built in the late 1950s and completed in 1959.[xiii] (This latter obsession would be published in 1972 as a children’s book, I’d Like the Goo-Gen-Heim.) By 1961, Hollingsworth began a series of mixed media paintings called Cry City that incorporated “materials of the ghetto – tar paper the artist found on tenement roofs; fishbones, broken cement, stones, teeth and bits of glass scrounged from the Harlem Streets.”[xiv] He continued to work on this series through 1965, when he showed twenty-six of the paintings in a solo exhibition at the Terry Dintenfass Gallery in New York City. The series’ focus was in part spurred by Hollingsworth’s participation from 1963 through 1965 with a coalition of black artists who called themselves “Spiral.”

“…when ‘Spiral’ came along, I really got involved. I had grown up in a gang era. Bopping clubs and fighting chiefs were everywhere. And it seemed to me that the pressures on minorities stemmed at least partially from urbanism – the crowding, the competition, the slums, the situations and conditions that the city creates. I felt that I could make a contribution through my feeling about the city.”

-Al Hollingsworth in Black Art – An International Quarterly, 1977

In July 1963 Hollingsworth, along with a several other younger artists, was invited to join a number of established painters led by Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Hale Woodruff and James Yeargans to discuss ways in which they might participate meaningfully in the upcoming March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, planned for August 28, 1963. They first gathered at Bearden’s Greenwich Village studio that he shared with Charles Alston. Additional members included Felrath Hines, Richard Mayhew, William Pritchard, Merton Simpson, Reginald Gammon, Calvin Douglas, Perry Ferguson, William Majors, Earle Miller and Emma Amos, the only woman. While many of the group attended the March as individuals, their purpose broadened to include discussions and explorations of their role as black artists in the broader civil rights movement.[xv]

Not since the Harlem Renaissance had such a group of artists been formed around a political, aesthetic, and social agenda.

-Sharon F. Patton “Cultural crisis: Black artist or American artist? Spiral artists’ group 1963-65”

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963, View from the Lincoln Memorial toward the Washington Monument. “US Government Photo.”

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was the idea of A. Philips Randolph, a black labor organizer, who had planned a similar march to protest segregation and discrimination in 1941 that had been cancelled. This time, he was joined by leaders of five major civil rights groups: Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Whitney Young of the National Urban League (NUL), James Farmer of Congress On Racial Equality, and John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), among others. More than 200,000 people attended the March, which culminated with Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech that called for racial justice and equality. The March paved the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

- Click to view an original program for the 1963 March and to find audio and video links to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s speech.

- Click for additional information on background and participants.

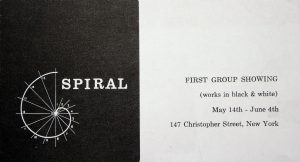

The group formalized under the name “Spiral,” suggested by Woodruff as a reference to the Archimedean spiral that ascends outward and upward in ever-broader circles. [xvi] Over a roughly two-year period, they discussed cultural identify and their role as black artists, attempted to define a black aesthetic, and supported each other through mentoring and sharing. The collective of artists rented a storefront at 147 Christopher Street as a meeting place and gallery and there installed their only group exhibition entitled “Spiral: First Group Showing (works in black and white),” on view from May 14 to June 5, 1965.

The group had planned to mount an earlier exhibit entitled “Mississippi 1964” and to create works to protest the violence and the murders of three civil rights activists that took place that year during the “Freedom Summer” voting registration project. [Hot link?] However, because of philosophical divisions within the group, they instead chose the black and white title as something more politically neutral and artistically unifying. “The participants did not want to be labeled ‘black artists’, nor to have their work categorized as ‘naively primitivist’ or ‘realist’. Yet each wished to identify and define their own relationship to their people’s struggle and to explore the possibility of conveying cultural significance through their art… Despite the original intention not to be overtly political, the black-and-white palette could not but symbolize race and imply the separation of white and black Americans. Hence this work, and the exhibition in general, foreshadowed the issue-oriented art of the late 1960s.”[xvii]

Exhibit catalogue as shown on pg. 224 of The Art of Romare Bearden (National Gallery of Art, 2003).

“We, as Negroes, could not fail to be touched by the outrage of segregation, or fail to relate to the self-reliance, hope, and courage of those persons who were marching in the interest of man’s dignity…if possible, in these times we hoped with our art to justify life…to use only black and white and eschew other coloration. This consideration, or limitation, was conceived from technical concerns; although the deeper motivations may have been involved…what is important now, and what has great portent for the future, is that Negro artists of divergent backgrounds and interests, have come together on terms of mutual respect. It is true to their credit that they were able to fashion art works lit by beauty, and of such diversity.”

-Spiral: First Group Showing (works in black and white),

Collective statement, exhibition catalog, May 14-15, 1965

Painter Romare Bearden suggested the group create and exhibit a collective project for the black and white show using the collage technique. His fellow artists did not support the idea, though Bearden himself did produce a series of photomontages made from magazine clippings that came to define his later style. Instead, the Spiralists each submitted works that ranged widely, from abstract expressionism to realism to social protest, all in black and white with the exception of Hollingsworth, who included the color brown in work from his Cry City series. The exhibition, therefore, reflected the differences in style, age, and philosophies that existed within the group from the beginning. These variances were also highlighted in an interview conducted by Jeanne Siegel of New York’s School of Visual Arts and published under the title “Why Spiral?” in the September 1966 issue of Art News, as well as in a panel discussion that Siegel conducted about the Spiral Group that was broadcast on WBAI in December 1967.[xviii]

Despite the differences of the artists and the short life of the coalition, the Spiral group had an impact on African-American art, if not the Civil Right movement. As member Richard Mayhew stated: “… like the spiral, it continues to extend, to engulf and encompass more and more black artists. As a result [of Spiral] many groups of artists have come together, and now Spiral has become a kind of unusual mystique among them, a symbol of unification and aesthetic values.”[xix]

Hollingsworth began his Cry City series about 1961 in an attempt “to capture the violence and erosive spirit of the city through its walls.”[xx] The work “grew out of the violence and turbulence of the early 1960s” that included the assassination of President John F. Kennedy; violent attacks on civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama; the murder of Medgar Evans in Jackson, Mississippi; and the riots in the Watts section of Los Angeles.[xxi] Hollingsworth’s mixed media paintings in the Spiral exhibition that included Why? Black Guernica and Composition No. 2 were among those considered protest art. “I had a statement to make and I made it,” he declared later in 1977 about the complete Cry City series that he showed at the Terry Dintenfass Gallery, also in 1965.[xxii]

________________________________

Al Hollingsworth and Don Quixote / Man of La Mancha: Reflections of an Era

Hollingsworth’s style varied widely as a young artist as he searched for his own voice. In addition to his training as a comic book illustrator, he was probably influenced by the work of white artist Robert Gwathmey, a social realist painter and teacher from Virginia known for his paintings of the American south, especially figures of African American workers. Gwathmey taught at Cooper Union (NYC) and Hollingsworth mentioned that he was aware of him as a child.[xxiii] During graduate school, Hollingsworth began to emulate the style of Nicholas De Stael and, during the 1960s, he was very aware of the New York art scene and knew Pop artist Tom Wesselman personally.[xxiv] Romare Bearden compared Hollingsworth to African American artist Harry O. Tanner in a review of his Prophet series exhibited in 1970.[xxv] Hollingsworth began these paintings of black biblical prophets in the late 1960s, following the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. The artist saw the figures in his work as “philosophical symbol[s] of any of the modern prophets who have been trying to show us the right way. To me, Malcom X and Martin Luther King are such prophets.”[xxvi]

While his style often varied, Hollingsworth was consistent in his serial exploration of themes. Cry City and The Prophet were only two examples. Subsequent themes that he explored included: The Women; Space, Time, Infinity; Sketches from the Subconscious; and series on dreams, dancers, jazz musicians, among others.[xxvii] Such repeated explorations may be rooted in Hollingsworth’s early work with serialized comic books.

For him, one painting cannot possibly say everything he wants to say. And, in his almost compulsive drive to produce and to keep producing, he has been known to turn out several hundred paintings, drawings and collages, all on a single subject, all distinctive, as if to demonstrate his seemingly endless versatility to himself and the world, but all unified around a central theme. Such a theme may take a long time to develop or refine and may represent many thousands of hours of hard physical labor, but for Hollingsworth, the theme is the thing.

-Hewitt, John H. Black Art – An International Quarterly, 1977

Man of La Mancha represents another of Hollingsworth’s thematic series, which he produced in various media over a decade or more. None of the work identified so far is dated, except for a lithograph entitled “The Trio” (Don Quixote, Sancho Panza, and Dulcinea) and inscribed 1979.[xxviii] However, as early as 1967 Hollingsworth had an exhibition entitled Man of La Mancha at ANTA Washington Square Theatre (American National Theater and Academy) in Greenwich Village, where the musical began its first New York run on November 22, 1965, before it moved to the Martin Beck Theatre in 1968.[xxix]

To fight for the right / Without question or pause / To be willing to march into Hell / For a heavenly cause…

-Excerpt from “The Impossible Dream,” music by Mitch Leigh and lyrics by Joe Darion

The musical and its story resonated with Hollingsworth, as well as with other African American leaders and artists. The song, “The Impossible Dream (The Quest)” was played at the funeral of Whitney M. Young, Jr. (1921-1971), Executive Director of the National Urban League, because it was one of his favorites. He carried the words in his wallet and quoted phrases of the song in his speeches. The Motown group The Temptations recorded “The Impossible Dream” in 1967 and sang it with the Supremes in a 1968 television special – perhaps an echo of the “I Have a Dream” speech delivered at the March on Washington by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was assassinated in April 1968.

Hollingsworth created numerous paintings and at least thirteen editions of lithographs on the theme of Don Quixote (Man of La Mancha), three of which are owned by Washington and Lee University. In addition, he is documented as creating murals for the Don Quixote Apartments located in the Bronx. The 1977 Black Arts interview does not mention the murals, but one source dates them to 1969.[xxx]

Hollingsworth was interested in mural painting as early as 1964, when he taught a workshop “Drawing for a mural cartoon” at the High School of Art and Design in which his students created three to six 3’ x 4 ‘ drawings on topics that included “Busy City,” “Campus of Art & Design,” “Freedom for All,” and “Abstraction on a Theme.”[xxxi] Harlem and other New York City neighborhoods like the Bronx were in the vanguard of a national mural movement, begun about 1968, in which artists brought art directly into their communities.[xxxii] The Don Quixote murals were made for the Don Quixote Apartments in the South Bronx and may have been part of or sparked by the Bronx Model Cities Neighborhood Plan (1968-1972), which was conceived to reduce blight, improve housing and education, create jobs and career opportunities, raise hope and better the lives of neighborhood residents.[xxxiii] Also part of the Bronx Plan 1968-72 was the expanded campus for the Eugenio Maria de Hostos Community College, which was centrally located and fulfilled one of the goals of the plan.[v] In 1985, Hollingsworth completed a mural for the community college entitled “Hostos Odessey.” Fifteen years earlier in 1970, he had also completed a mural on the life of singer Paul Robeson for the Robeson Center at Rutgers University.[xxxiv]

For twenty-seven years Hollingsworth taught at Hostos Community College, from 1971 until his retirement in 1998. Teaching was a passion. He taught in the New York Public School system, at the Pan American Art School, and at the High School of Art and Design before teaching in college. He supervised the New York City Board of Education “Project Turn-on,” which created teaching programs and art demonstrations.[xxxv] He wrote and moderated three television series: You’re Part of Art (1971); You’ve Gotta Have Art (1977); and The Creative Years of the Child (1980), bringing art to the community through mass media. He illustrated books, including Black Out Loud: An Anthology of Modern Poems by Black American ; Journey (part of Scholastic Books’ Black Literature Series); and I’d Like the Goo-Gen-Heim, the latter which has been reprinted and is still available through the Guggenheim Museum Store. His interest in youth went beyond the classroom; Hollingsworth was married with six children of his own.

By the 1980s, Hollingsworth’s activities were described as “peripatetic” and creating a handicap in his creative development.[viii] Despite this criticism, Hollingsworth left an important legacy, especially as a member of Spiral.

Its members continued to work, exhibit, teach, and support younger artists. They touched the lives of many and left a solid body of work. In their respective ways, the artists of Spiral drew upon their multiple identities and cultural heritages to create inventive and powerful art that would accord them a central place in the history of modern American art. The artists who banded together under the Archimedean symbol of all-encompassing change paved the way for those African-American artists who followed, if not in their footsteps, at least in the broad paths they cleared Thus, the legacy of Spiral will expand and remain secure for generations to come..[ix]

Hollingsworth’s work can be found in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture; The Hewitt Collection of African-American Art, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture; as well as numerous academic, corporate, and private collections.

Timeline: Alvin Carl Hollingsworth (1928-2000)

1942: Employed at Holyoke Publications by the age of 14, and the first African American artist hired by Fawcett.

1946: Graduated from the High School of Music and Art, NYC.

1950: Continued studies at the Art Students League, while continuing as a comic book illustrator.

1954: Produced his own comic strip “Kandy” for the Pittsburgh Courier/Smith-Mann Syndicate.

1956: Graduated from City University of New York; first group exhibition at the 45th Annual Newport Art Association Show.

1957: Worked as art editor at Fooey magazine and contributor at Thimk [sic].

1958: Taught at Paul Hoffman Jr. High School and began working with ultraviolet light on fluorescent material.

1959: Received MA, City College of New York.

1961: Taught at ps45 in the Bronx and was a graphics instructor at the High School of Art & Design for ten years; first solo show at Ward Eggleston Gallery, NYC, and part of group exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum.

1963: Worked for the publication Manhattan East; taught at the Pan American Art School; became a member of Spiral Group; won an Emily Lowe Art Award.

1964: First exhibition of Spiral Group at the Christopher Street Gallery; won a Whitney Foundation Award.

1965: Dintenfass Gallery exhibition featured Hollingsworth’s use of fluorescent materials.

1966-68: Served as director at the Lincoln Institute of Psycho-Therapy Art Gallery.

1967: Hollingsworth’s Man of La Mancha exhibition at ANTA Washington Square Theatre, NYC; designated “Artist of the Year” at NYU.

1968-69: Served as supervisor of art at Project Turn-On, in New York.

1969-75: Painting instructor at the Art Students League.

1970: Ph.D. candidate at the School of Education of New York University; completed mural for the Paul Robeson Lounge at Rutgers University; wrote and hosted the television series, You’re Part of Art on WNBC; published I’d Like the Goo-Gen-Heim (author and illustrator); illustrated Black Out Loud: An Anthology of Modern Poems by Black Americans

1971: Received Award of Distinction from the Smith-Mason Gallery; featured in Ebony magazine in “Artists Portray a Black Christ”; participated in Whitney Museum of American Art Contemporary Black Artists in America exhibition.

1971–98: Taught at and retired from Eugenio Maria de Hostos Community College of the City University of New York

1977: Wrote and hosted the television series, You’ve Gotta Have Art

1980: Wrote and hosted the television series, The Creative years of the Child

1985: Completed a mural for Hostos Community College entitled, ‘Hostos Odessey”

1998: Retired from Hostos Community College

music by Mitch Leigh and lyrics by Joe Darion

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

To right the unrightable wrong

To love pure and chaste from afar

To try when your arms are too weary

To reach the unreachable star

This is my quest

To follow that star

No matter how hopeless

No matter how far

To fight for the right

Without question or pause

To be willing to march into Hell

For a heavenly cause

And I know if I’ll only be true

To this glorious quest

That my heart will lie peaceful and calm

When I’m laid to my rest

And the world will be better for this

That one man, scorned and covered with scars

Still strove with his last ounce of courage

To reach the unreachable star

For further discussion

1. The Iconic Don Quixote in Literature and Pop Culture

Whatever Cervantes’ initial idea, in the course of the last 400 years, Don Quixote has embarked on a journey in the world imagination that has taken the literary character far beyond its original conception. The book illustrations of Cervantes’ Don Quixote would play a decisive role in this — transforming not only the image of Don Quixote and his loyal servant Sancho Panza but also by giving life to the image of Cervantes himself. (-Rachel Schmidt, “Picturing Don Quixote,” The Public Domain Review, Web, January 9, 2017)

Pre-Discussion: To build critical thinking through images, show students each of the three lithographs by Alvin Hollingsworth one by one so that they will:

- Look carefully at the works of art;

- Talk about what they observe;

- Back up their ideas with evidence;

- Listen to and consider the views of others; and

- Discuss and hold as possible a variety of interpretations.

For each, have them answer the following questions:

- What is going on in this picture?

- What do you SEE that makes you say that?

- What more can you find?

At this point, do not have them draw any conclusions about the works. Keep the discussion open-ended.

- For more information on Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) that develop critical thinking and communication skills, see the Visual Thinking Strategies website.

- For the value of using the teaching method on a university level, see the Academy for Thinking and Learning website.

After examining the prints, have students read the following:

- Brief excerpts from Don Quixote part I that describe the physical characteristics of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, as well as the episode of tilting at windmills. (PDF link from: Cervantes Project, Texas A&M. 1995, Web, 9 Jan. 2017)

- Rachel Schmidt, “Picturing Don Quixote,” The Public Domain Review, Web, 9 Jan. 2017.

Discussion:

- What points does Schmidt make regarding the role art has played in transforming the images of Cervantes’ characters, especially Don Quixote? She mentions a “multiplicity of visual interpretations.” What does she mean by this? Do Hollingsworth’s illustrated characters fit into her argument and, if so, how?

- Compare and contrast Hollingsworth’s depiction of Cervantes’ characters to those of other more modern artists:

- Honoré Daumier (See the National Gallery website).

- Gustave Doré (See the Open Culture website).

- Salvador Dali (See “Salvador Dalí Ilustrates Don Quixote” on Brainpickings.org).

- Pablo Picasso (See “Pablo Picasso’s Don Quixote Lithograph Signed by Hand in Pencil” on Picassoclub.com).

style=”color: #0c71c3;”> 2. Alvin Carl Hollingsworth: Rooted in Harlem

The Harlem Renaissance was the name given to the cultural, social, and artistic explosion that took place in Harlem between the end of World War I and the middle of the 1930s. During this period Harlem was a cultural center, drawing black writers, artists, musicians, photographers, poets, and scholars. Many had come from the South, fleeing its oppressive caste system in order to find a place where they could freely express their talents. Among those artists whose works achieved recognition were Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, Countee Cullen and Arna Bontemps, Zora Neale Hurston and Jean Toomer, Walter White and James Weldon Johnson. W.E.B. Du Bois encouraged talented artists to leave the South. Du Bois, then the editor of THE CRISIS magazine, the journal of the NAACP, was at the height of his fame and influence in the black community. THE CRISIS published the poems, stories, and visual works of many artists of the period. The Renaissance was more than a literary movement: It involved racial pride, fueled in part by the militancy of the “New Negro” demanding civil and political rights. The Renaissance incorporated jazz and the blues, attracting whites to Harlem speakeasies, where interracial couples danced. But the Renaissance had little impact on breaking down the rigid barriers of Jim Crow that separated the races. While it may have contributed to a certain relaxation of racial attitudes among young whites, perhaps its greatest impact was to reinforce race pride among blacks.

— Richard Wormser, Jim Crow Stories: The Harlem Renaissance on PBS.org

Pre-Discussion:

For more information, see:

- “The Harlem Renaissance” on History.com.

- “A Guide to Harlem Renaissance Materials” on the Library of Congress website.

- An online exhibition on the Harlem Renaissance at the New York Public Library.

Discussion:

By 1928, when Hollingsworth was born, the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. Two years earlier in 1926, Langston Hughes published his first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues. Two of his poems referenced dreams – a theme that Hollingsworth would later explore as an artist, including his Don Quixote lithograph entitled “Dream the Impossible Dream.”

- Students read the following poems by Hughes and analyze each and explain the poet’s use of “dreams” in the context of the historical era (Great Migration, Harlem Renaissance, Jim Crow, etc.).

Dreams

Langston Hughes (1902 – 1967)

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow.

Dream Variations

Langston Hughes (1902 – 1967)

To fling my arms wide

In some place of the sun,

To whirl and to dance

Till the white day is done.

Then rest at cool evening

Beneath a tall tree

While night comes on gently,

Dark like me—

That is my dream!

To fling my arms wide

In the face of the sun,

Dance! Whirl! Whirl!

Till the quick day is done.

Rest at pale evening . . .

A tall, slim tree . . .

Night coming tenderly

Black like me.

Studio Exercise:

Have students create at least two drawings, prints or paintings (medium of their choice) that are inspired by Hughes’ poetry and Hollingsworth’s lithographs.

3. A.C. Hollingsworth (AKA Alvin Holly): Comic Book Illustrator

C. Hollingsworth with George Shedd, Martin Keel, 1950s, Source: Lambiek.net

C. Hollingsworth with George Shedd, Martin Keel, 1950s, Source: Lambiek.net

Hollingsworth trained as a comic book artist and graphic illustrator before he went on to work as a fine artist. His work in both arenas, which might be termed low and high art, respectively, is most often narrative.

Comic books, like those illustrated by Alvin Hollingsworth (identified as A.H.C., A.C., Alvin Holly, Alec Hope, as well as under his own name) are sequenced visual narratives that involve the following skills which might be performed by one or several individuals.

- Draftsman, the person who draws the initial layout in pencil

- Inker, also known as “ink slinger,” who adds ink over the drawing

- Colorist, who adds color to the inked work

The artwork is then reproduced mechanically on inexpensive paper for broad distribution. It is art for the masses.

Hollingsworth’s lithographic prints could also be produced collaboratively, but the artistic process is more individualistic and variable, and the final work is a smaller edition distributed through a gallery to a limited buying public.

A traditional lithograph like Hollingsworth’s Attack at Dawn is produced using a lithographic stone, which is a slab of limestone. The steps to produce the print include:

- Drawing an image using an oil-based crayon or a greasy ink called tusche, then wiping the stone with a chemical solution that causes the image to attract ink and the blank areas to repel ink

- Fixing an image by wiping stone with a solvent to dissolve the original drawing; a greasy ghostlike image remains

- The stone is dampened with water which is absorbed by the blank areas and ink is rolled onto the surface of the stone, adhering only to the image

- The stone is then placed on the bed of a lithographic press, damp paper is placed on top of the stone, and they are rolled by hand through the press

- The finished print is lifted off the stone and set aside to dry.

- The process continues for the limited number of prints called an edition and determined by the artist. Hollingsworth’s print Attack at Dawn is an edition of 250 prints.

(Steps are taken from MOMA’s “What is a Print?” interactive.

Pre-Discussion:

- Students view and examine closely several pages from Hollingsworth’s comic book Negro Romance at PBS.org; Other comic book covers by Hollingsworth can be viewed at The Comic Collector Live website.

- Students view the videos on the process of creating a lithograph, see:

- Pressure + Ink: Lithography Process, a MoMA interactive video.

- Stone Lithography at Edinburgh Printmakers.

Discussion:

- Students compare and contrast Hollingsworth’s lithograph Attack at Dawn to his comic book work in terms of the following:

- Composition

- Use and quality of line

- Use of color

- Narrative elements

- Quality and quantity

- Students discuss how Don Quixote and Sancho Panza in Hollingsworth’s print might relate to a superhero in comics such as Superman? Note that there are several comic book versions of Don Quixote; one can be found at Comic Books Online.

4. Al Hollingsworth, the Spiral Group, and the 1960s Civil Right Movement

A. Students read: “The Changing Same: Spiral, the Sixties, and African-American Art,” by Floyd Coleman in William E. Taylor and Harriet G. Warkel, eds., A Shared Heritage: Art by Four African Americans (Bloomington, IN: The Indianapolis Museum of Art, distributed by Indiana University Press, 1996), 148-157. [Leyburn Library Level 3 Cat. No. N 6538.N5 T37 1996].

- Summarize in your own words what Coleman states is the significance of the Spiral group to the history of art and to the Civil Rights Movement.

- How does Coleman relate the works of the Spiral Group to the literary work of Ralph Ellison?

B. Hollingsworth’s lithograph “Dream the Impossible Dream” illustrates literary characters created by Spanish writer Cervantes and is titled after a popular American mid-20th century Broadway show tune that had resonance for the era.

- Students read the lyrics from the song.

- Students read the essay, “The Man of La Mancha” by Scott Miller, New Line Theatre’s artistic director.

- Students write an essay explaining how Man of La Mancha reflected the era of the 1960s. How might it relate to our world today?

C. Consider the definition of dreams in the following exercises:

- The term “American Dream” was coined by James Truslow Adams in his 1931 book The Epic of America. Students read a short essay that incorporates Adams’ definition in What is the American Dream? at this Library of Congress article.

- After reading the above essay, students read the following lyric poem “Harlem” by Langston Hughes, first published in 1951. (They can also listen to it read by Danny Grover as part of a May 2, 2007, reading from “Voices of a People’s History of the United States” (Howard Zinn and Anthony Arnove).

Harlem

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

Like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

Like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Langston Hughes 1951

- Students write an essay explaining how Man of La Mancha reflected the era of the 1960s. How might it relate to our world today? How do Hollingsworth’s lithographs relate to the musical and to the 1960s and 1970s?

In his speech delivered on August 28, 1963 at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. outlined the economic and social limitations that plagued African Americans at a time “when the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.” King transitions to the most memorable part of his speech with the words: “And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

- Students read the speech in its entirety. You can find links to the text in addition to audios and visuals at:

- “Official Program for the March on Washington (1963)”

- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom“

- Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech

- Students describe what Dr. King outlines as his dream. Does it echo James Truslow Adams definition of the American Dream? If so, explain how. Was this an “impossible dream?” Explain.

- One of the favorite contemporary songs from the 1960s for Whitney Young, Jr., Executive Director of the National Urban League and one of the organizers of the 1963 March on Washington, was “The Impossible Dream” from Man from La Mancha. Students reread the song lyrics or listen to Motown interpretations of the song. Explain why the song was important to Young and others within the Civil Rights Movement. (YouTube videos: “The Impossible Dream” by Diana Ross and the Temptations and another version here.)

- Does Hollingsworth’s lithograph reflect the idea of “The Impossible Dream”? If so, how?

E. In 1966, Jeanne Siegel –– writer, essayist, art critic, and educator with the School of Visual Arts ––interviewed 14 of the members of the Spiral collective. She asked them about their purpose, as well as about civil rights, “Negro art,” and the “Negro Image.” In her introduction, she states “When I asked each of the 13 men and one woman that make up the present membership of the Spiral group what Spiral stands for, I got 14 conflicting answers.”

A year later, Siegel moderated a follow-up radio interview with Spiral members Romare Bearden, William Majors, and Alvin Hollingsworth and asked them, “In retrospect, how effective were the paintings in the Spiral Exhibition as social protest art?”

- Students read these essays:

- “‘Why Spiral?’: Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, and Others on the ‘Contradictions Facing Them in Modern America’ in 1966,” ArtNews.

- Siegel, Jeanne. “How Effective is Social Protest Art? (Civil Rights)” [transcript of a panel discussion between Bearden, Hollingsworth, and Majors, moderated by Jeanne Siegel, originally broadcast on Dec. 14, 1967 on WBAI]. Artwords: discourse on the 60s and 70s. UMI Research Press, c1985, pp. 84-98. [Leyburn Library Level 3, Call No. N6490 .S496 1985)

- Students discuss the Spiral members’ attitudes towards protest art and explain their attitudes about Pop art as protest art.

- Students stage a panel discussion to debate the concept of “protest art” in the 20th century and compare it to the 21st. To prepare, students must conduct preparatory research.

5. Al Hollingsworth and Don Quixote / Man of La Mancha: Reflections of an Era

Studio Exercise: Students design a series of murals that reflect events of this current academic year.

Review images of NYC murals using one or both of the following sources:

- On the Wall: Four Decades of Community Murals in New York City. Authors Janet Braun-Reinitz and Jane Weissman describe the origin and evolution of New York murals from the late 1960s to the present, which they illustrate with photographs of work in situ, as well. The book is available in Leyburn Library Level 3, Call No. ND2638.N4 B63 2009.

- You can view more contemporary NYC murals online at: Howard Halle and Kenny Herzog, “The top 10 spots to see graffiti in NYC,” TimeOut New York, 29 Dec. 2015. Web. (January 11, 2017)]

Complete three to four drawings, following instructions for Alvin Hollingsworth’s class “Drawing for a mural cartoon:”

- Select a theme for your SERIES of murals from the following list:

- Small City: Lexington

- W&L Campus

- Freedom for All

- Abstraction on a Theme

- Don Quixote

- Develop preliminary drawings for the series in a sketchbook

- Gather drawing media (pencil, graphite, conté crayon, charcoal, pastel, pen and ink)

- Prepare three to six 3’ x 4’ surfaces on which to draw (paper, cardboard, matboard, etc.)

- Execute the drawings

Notes:

[i] “History Detectives: African American Comic Book.” Season 9, Episode 4, Story 3 – Negro Romance, co-produced for PBS by Oregon Public Broadcasting and Lion Television, http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/the-golden-age-of-comics/ (September 8, 2016).

[ii] Tim Jackson, “1940-1949: The Cartoon Renaissance” in Pioneering Cartoonists of Color (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 55.

[iii] Alex Jay, “Ink-Slinger Profiles: A.C. Hollingsworth,” Strippers Guide, February 25, 2012, http://strippersguide.blogspot.com/2012/02/ink-slinger-profiles-ac-hollingsworth.html?m=1 (February 26, 2016

[iv] Jackson 53

[v] Jackson 95

[vi] Jackson 105.

[vii] Jackson 11.

[viii] “Pop Culture,” Dictionary.com. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/popular-culture (January 10, 2017)

[ix] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, reprint 1994) 20

[x] John H. Hewitt, “The Themes of Alvin C. Hollingsworth,” Black Art – An International Quarterly 2:1 (1977): 15

[xi] Alvin C. Hollingsworth, “Teaching Art to the Gifted in a New York High School,” American Artist (June 1964): 68,101.

[xii] Hewitt, 5

[xiii] Elsa Honig Fine, “Blackstream Artists,” The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1982) 248-249.

[xiv] Hewitt, 5

[xv] Floyd Coleman, “The Changing Same: Spiral, the Sixties, and African-American Art,” in William E. Taylor and Harriet G. Warkel, eds., A Shared Heritage: Art by Four African Americans (Bloomington, IN: The Indianapolis Museum of Art, distributed by Indiana University Press, 1996), 148-157.

[xvi] Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, “The Development of Spiral” and “Richard Mayhew,” A History of African-American Artists from 1792 to the Present (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), 400.

[xvii] Sharon F. Patton, “Cultural crisis: Black artist or American artist? Spiral artists’ group 1963-6” in “Twentieth-Century America: The Evolution of a Black Aesthetic,” African-American Art. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 186-187.

[xviii] Jeanne Siegel, “Why Spiral?” Art News, 65:5 (September 1966), 48-51 and “How Effective is Social Protest Art? (Civil Rights)” [transcript of a panel discussion between Bearden, Hollingsworth, and Majors, moderated by Jeanne Siegel, originally broadcast on Dec. 14, 1967 on WBAI] in Artwords : discourse on the 60s and 70s (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, c1985), 84-98.

[xix] Bearden and Henderson, 403.

[xx] Siegel, Artwords, 87

[xxi] Hewitt, 5

[xxii] Hewitt, 5

[xxiii] Siegel, Art News, 49

[xxiv] Hewitt, 16; Siegel, Artwords, 89

[xxv] Hewitt, 6

[xxvi] Peter Bailey, “Artists Portray a Black Christ,” Ebony, 26: 6. April 1971, 177.

[xxvii] Hewitt, 5, 8, 11, 17

[xxviii] “Lithograph A.C. Hollingsworth ‘Trio’ Don Quixote series,” Worthpoint, http://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/lithograph-hollingsworth-trio-don-74642944 (August 2, 2016)

[xxix] “Hollingsworth, Alvin Carl… Bibliography and Exhibitions.” African American Visual Artists Database, 2006, http://216.197.120.164/artistbibliog.cfm?id=433 (January 7, 2017)

[xxx] “Alvin Carl HOLLINGSWORTH (1928-2000),” Artprice, http://www.artprice.com/artist/192803/alvin-carl-hollingsworth (August 11, 2016).

[xxxi] Hollingsworth, 99.

[xxxiii] Janet Braun-Reinitz and Jane Weissman, On the Wall: Four Decades of Community Murals in New York City (University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 3.

[xxxiv] Jonas Vizbaras, Bronx Plan 1968-72: A Report on the Bronx Model Cities Neighborhood, Office of the Mayor, New York., Model Cities Administration (1972), 2. https://openlibrary.org/books/ia:reportonbronxmod00jona/Report_on_the_Bronx_Model_Cities_Neighborhood (January 11, 2017).

[xxxv] Vizbaras, 37.

[xxxvi] Jay, Strippers Guide; and Helen Paxton. “Artwork to discover: The Rutgers-Newark collection is seen in all the right places,” Rutgers Focus, Rutgers University (Feb 9, 2001), http://urwebsrv.rutgers.edu/focus/article/Artwork%20to%20discover/638/ (January 7, 2017).

[xxxvii] Fine, 247.

[xxxviii] Fine, 247.

[xxxix] Coleman, 157.

Selected bibliography for further reading

The Iconic Don Quixote in Literature and Pop Culture

- Faires, Robert. “Man of La Mancha.” The Austin Chronicle. 14 Sept. 2001. Web. 28 Nov. 2016. Hot link to: http://www.austinchronicle.com/arts/2001-09-14/82898/

- Jones, John Bush. “Issue-Driven Musicals of the Turbulent Years: The Seeds of the Sixties,” Chapter 7 in Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical Theatre. Brandeis University Press, University Press of New England, 2003, pp. 235-268.

- Man of La Mancha: Synopsis. Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc. Web. 28 Nov. 2016. Hot link to: http://www.tamswitmark.com/shows/man-of-la-mancha/

- Miller, Scott. “Inside Man of La Mancha.” New Line Theatre. 1996-2004. Web. 28 Nov. 2016. Hot link to: http://www.newlinetheatre.com/lamanchachapter.html

- Schmidt, Rachel. “Picturing Don Quixote,” The Public Domain Review. 2016. Web. 10 Dec. 2016. Hot link to: https://publicdomainreview.org/2016/04/06/picturing-don-quixote/

- Wasserman, Dale. The Impossible Musical: The Man of La Mancha Story. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2003.

Synopses and study guides about Cervantes’ Don Quixote have been published online for various grade levels and can be used for inspiration in the classroom. Study guides for both the musical and film Man of Le Mancha, including college level, can also be found in abundance. Examples include:

- Alcalà-Galan, Mercedes et al. Don Quixote in Wisconsin: Teaching Materials. Great World Texts in Wisconsin Program of the Center for the Humanities (Madison: University of Wisconsin). Web. November 28, 2016. Hot link to: http://humanities.wisc.edu/assets/misc/DQ_in_WI_complete_guide.pdf

- Galindo, Alberto S. Study Guide for El Quijote by Santiago García. Repertorio Español 2006. Web. 28 Nov. 2016. Hot link to: http://rep138.tempdomainname.com/education/pdfs/quijote.pdf

- Man of La Mancha – Study Guide [Film]. Applause Learning Resources. Web. 28 Nov. 2016. Hot link to: http://www.applauselearning.com/MAN-OF-LA-MANCHA-STUDY-GUIDE/productinfo/TL282/

A.C. Hollingsworth (AKA Alvin Holly): Comic Book Illustrator

- Gavaler, Chris. “Top 8 Superhero Comics, 1934-1971.” The Patron Saint of Superheroes. 19 Sept. 2016. Web. 10 Dec. 2016. https://thepatronsaintofsuperheroes.wordpress.com/

- “History Detectives: African American Comic Book.” Season 9, Episode 4, Story 3 – Negro Romance. Co-produced for PBS by Oregon Public Broadcasting and Lion Television. 8 Sept. 2016. http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/investigation/african-american-comic-book/

- “History Detectives: The Golden Age of Comics.” co-produced for PBS by Oregon Public Broadcasting and Lion Television. 8 Sept. 2016. http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/the-golden-age-of-comics/

- Jackson, Tim. “1940-1949: The Cartoon Renaissance.” Pioneering Cartoonists of Color. University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

- Jay, Alex. “Ink-Slinger Profiles: A.C. Hollingsworth.” Strippers Guide. 25 Feb. 2012. 26 Feb. 2016. http://strippersguide.blogspot.com/2012/02/ink-slinger-profiles-ac-hollingsworth.html

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins Publishers, 1994 reprint.

The Spiral Group

- Bearden, Romare and Harry Henderson. “The Development of Spiral” and “Richard Mayhew.” A History of African-American Artists From 1792 to the Present. Pantheon Books, 1993, pp. 400-403; 474-477

- Coleman, Floyd. “The Changing Same: Spiral, the Sixties, and African-American Art.” A Shared Heritage: Art by Four African Americans, edited by William E. Taylor and Harriet G. Warkel. The Indianapolis Museum of Art: distributed by Indiana University Press, 1996, pp. 147-158.

- Marcella F. “The Spiral Collective and Civil Rights Art.” Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. 8 Nov. 2013. Web. 27 Feb. 2016. http://nmaahc.tumblr.com/post/66398447364/the-spiral-collective-and-civil-rights-art

- Patton, Sharon F. “Twentieth-Century America: The Evolution of a Black Aesthetic.” African-American Art. Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 183-190

- Siegel, Jeanne. “How Effective is Social Protest Art? (Civil Rights)” [transcript of a panel discussion between Bearden, Hollingsworth, and Majors, moderated by Jeanne Siegel, originally broadcast on Dec. 14, 1967 on WBAI]. Artwords : discourse on the 60s and 70s. UMI Research Press, c1985, pp. 84-98.

- – – -. “Why Spiral?” Art News 65, 5 (September 1966), pp. 48-51; “’Why Spiral?’: Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, and Others on the ‘Contradictions Facing Them in Modern America,’ in 1966.” Art News. 12 Dec. 2015. Web. 9 Nov. 2016. http://www.artnews.com/2015/12/12/september-1966-norman-lewis-romare-bearden/

- Valentine, Victoria L. “Romare Bearden, Spiral Group and the March Toward Artistic Identity.” Culture Type. 28 Aug. 2013. Web. 27 Feb. 2016. http://www.culturetype.com/2013/08/28/romare-bearden-spriral-group-and-the-march-toward-artistic-identity/

Al Hollingsworth

- Bailey, Peter. “Artists Portray a Black Christ.” Ebony, 26: 6. April 1971, pp. 177-180.

- Fine, Elsa Honig. “Blackstream Artists.” The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity. Hacker Art Books, 1982, pp. 247-249

- Hewitt, John H. “The Themes of Alvin C. Hollingsworth.” Black Art – An International Quarterly, 2:1. Black Art, LTD., 1977.

- “Hollingsworth, Alvin Carl… Bibliography and Exhibitions.” African American Visual Artists Database. 2006. Web. 7 January 2017. http://216.197.120.164/artistbibliog.cfm?id=433

- Hollingsworth, Alvin C. “Teaching Art to the Gifted in a New York High School.” American Artist, June 1964, pp. 68-73, 90-101.

- Lewis, Samella. African American Art and Artists. University of California Press,1990, pp.176-178.

- You’re Part of Art.” Art of the Print. Web. 26 Feb. 2016 http://www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/hollingsworth_alvin_carl_part_art.htm

Created by Patricia A. Hobbs, Associate Director and Curator of Art and History, University Collections of Art & History, Washington and Lee University. Thanks also to Brittany Lloyd, WL’15, for initial research assistance.

This lesson can be used or adapted by other educators for educational purposes with attribution to Hobbs. None of this material may be used for commercial purposes. Copyright of original artworks belongs to the artist. Reproduced with permission from the artist. Please contact Andrea Lepage for information the Teaching with UCAH Project: lepagea@wlu.edu or (540) 458-8305. Toolkit Lesson for Alvin Hollinsgworth by Patricia Hobbs is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.