Ekphrastic Poetry—A Unit for a Creative Writing Seminar

Laura Brodie, Department of English

Downloads: Faculty Notes | PowerPoint Presentation with Related Images

“Ekphrasis” is an obscure word for a common phenomenon: the impulse of artists of various media to compose creative responses to other artists’ work. In Greek, the word translates roughly into “description,” and “ekphrastic writing” is often defined as writing that describes an artistic product. However, description is only one among many elements in a successful piece of ekphrastic writing. What follows is an outline for a three-day unit in a creative writing class, designed to introduce students to the writing of ekphrastic poetry. The final assignment requires students to apply their knowledge of ekphrastic writing to works within the Washington and Lee collection. The course could easily be adjusted to cover ekphrastic prose, with an altered set of readings.

In English departments, when we discuss ekphrastic poetry, the most common example is John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” sometimes supplemented with his sonnet, “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles.” However, the language in those poems can be difficult for non-English majors. The following unit employs examples from modern poetry, to demonstrate a variety of twentieth-century poetic responses to art, in a format easily accessible to undergraduates.

DAY ONE

We begin with a mini-lecture focused on a simple question: what is “ekphrasis” and “ekphrastic writing”? The term “ekphrasis” comes from the Greek word for description, and ekphrastic writing often includes a description of a work of art. However, when an art historian describes a painting in a scholarly article, she would rarely characterize her work as ekphrastic writing. Something beyond straightforward description must take place. Ekphrastic poetry involves a meeting of creative minds—the poet meets the artist halfway, offering a creative response to the artist’s work.

When creative writing students write a response to a work of art, what kinds of writing can they produce, other than pure description? Let’s try it and see.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, Saint Rémy, June 1889. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/4″ (73.7 x 92.1 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo taken by Wally Gobetz, December 12, 2014. Used under a Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

The students’ first task is to consider an iconic painting familiar to most undergraduates: Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. After viewing The Starry Night on screen, the students will be instructed to take out a sheet of paper and write whatever thoughts the painting inspires—anything at all, so long as they produce words on the page—in prose or poetry. (At this point the instructor must be careful not to suggest types of responses that students might have to a painting—that will come later. With too much guidance, many students would simply follow suggestions rather than using their imaginations.)

Once the students have been given twenty minutes for in-class writing, volunteers will be asked to share their work. In listening to several examples of student writing, the class has one goal: try to come up with adjectives to describe the types of responses people have to works of art. Typical adjectives the class might produce include: emotional, descriptive, analytical, anecdotal, comparative, personal. Hopefully the students’ writing will contain enough variety to demonstrate that ekphrastic impulses can take a vast number of forms, as individual as each human being.

Rollie McKenna, Anne Sexton, 1961 (printed later). Gelatin silver print, Image: 34.3 x 26.5cm (13 1/2 x 10 7/16″). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Rollie McKenna. © 1961 Rollie McKenna. Digital Public Library of America.

Anne Sexton’s Response to Van Gogh’s Starry Night

Next, we will look at how the twentieth-century American poet, Anne Sexton, responded to Van Gogh’s painting.

The Starry Night

That does not keep me from having a

terrible need of — shall I say the word — religion

Then I go out at night to paint the stars.

–Vincent Van Gogh in a letter to his brother

The town does not exist

except where one black-haired tree slips

up like a drowned woman into the hot sky.

The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die.

It moves. They are all alive.

Even the moon bulges in its orange irons

to push children, like a god, from its eye.

The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die:

into that rushing beast of the night,

sucked up by that great dragon, to split

from my life with no flag,

no belly,

no cry.

After a student reads the poem aloud to the class, we will analyze it together—noting, for example:

- the possible purpose of the epigraph;

- the role of each of the three stanzas;

- the use of free verse with occasional rhyme,

- structured by repetition;

- the emphasis on violence and death,

- etc.

At this point the students will receive a brief mini-lecture on Anne Sexton’s biography, with an emphasis on her mental illness and obsession with death, and her ultimate suicide. This will be followed by brief information about Van Gogh’s struggles with mental illness, the context in which he produced The Starry Night, and his suicide.

Sexton has been called a confessional poet, known for her emotional, autobiographical, and often violent style. Her work demonstrates how ekphrastic writing can be emotive and deeply personal. But there are many other types of ekphrastic responses that the students can experiment with.

Day one homework

Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

For their homework, the students will be asked to write a rough draft of an ekphrastic poem in response to Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. Before seeing this work, they will be given, verbally, a brief overview of the biography of Pieter Brueghel and the myth of Icarus. Then, in the remaining class time, they will examine the painting on screen.

Their task is to study the painting inside and outside of class, then write a poem to bring to our next meeting. They may use the internet to learn more about Brueghel and Icarus, and to introduce any factual details needed for their poems, but this is not a research paper or an analytical piece. Their responses might be emotive or personal, though they will probably find the painting to be less emotionally evocative than The Starry Night. Students should bring two copies of their work to the next class-one for the instructor and one to share with a classmate.

Copy after Pieter Bruegel original., Landscape with the Fall of Icarus., c. 1560s. Oil on canvas (73.5 by 112 centimeters (28.9 in × 44.1 in)) in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels. Photo taken by Jim Forest,January 26, 2012. Used under a Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

DAY TWO

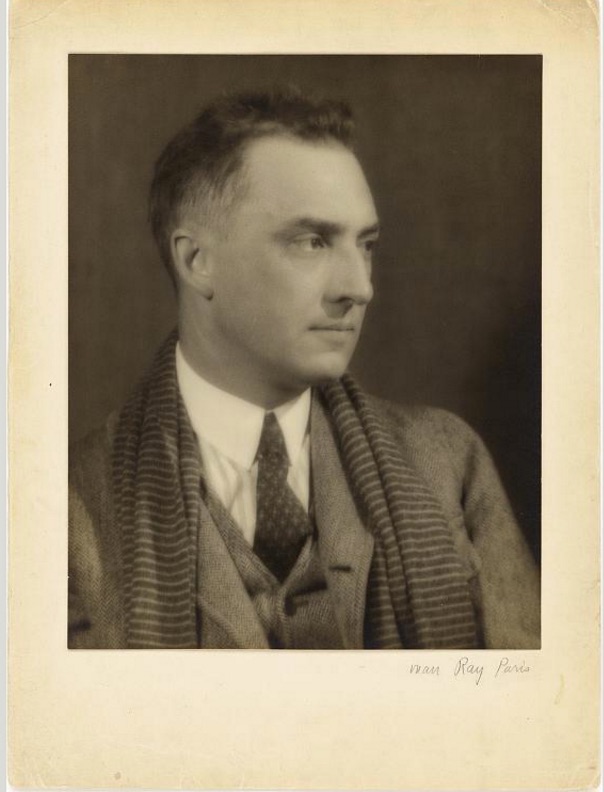

Man Ray, William Carlos Williams, 1924. Gelatin silver print, Image: 28.4 x 22.7cm (11 3/16 x 8 15/16″). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. © 2012 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society, NY / ADAGP, Paris. Digital Public Library of America.

William Carlos Williams’s Response to Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

We will begin by working in pairs, with the students exchanging their writing. If there is an odd number of students, one student will be paired with the instructor. The students will critique each other’s work, beginning with each poem’s strengths, followed by suggestions for improvement.

The students will be asked to characterize their classmates’ style of ekphrasis. Is their response to the painting descriptive, emotive, autobiographical, or something else? As on day one, we will hopefully discover a variety of ekphrastic styles in the students’ work.

We will then compare and contrast two modern poets’ responses to Brueghel’s painting: William Carlos Williams’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” and W. H. Auden’s “Musee des Beaux Arts.”

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

Is this even poetry? Consider Williams’s poem if it were written out in standard prose:

According to Brueghel, when Icarus fell it was spring. A farmer was ploughing his field. The whole pageantry of the year was awake, tingling with itself, sweating in the sun that melted the wings’ wax unsignificantly. Off the coast there was a splash, quite unnoticed. This was Icarus drowning.

How does Williams’s version turn these words into poetry? The class might discuss the impact of Williams’s short lines, why he decides to end each line where he does, the choice to omit most punctuation, the directness and simplicity of his style, his philosophy of “no ideas but in things,” and the extent to which this poem nevertheless has a central idea—or a central message about human tragedy.

Williams does not introduce himself, or emphasize his emotions, within the poem. He offers a style of ekphrasis very different from Anne Sexton’s. What adjectives might be used to describe Williams’s approach. Minimalist? Descriptive? Condensed?

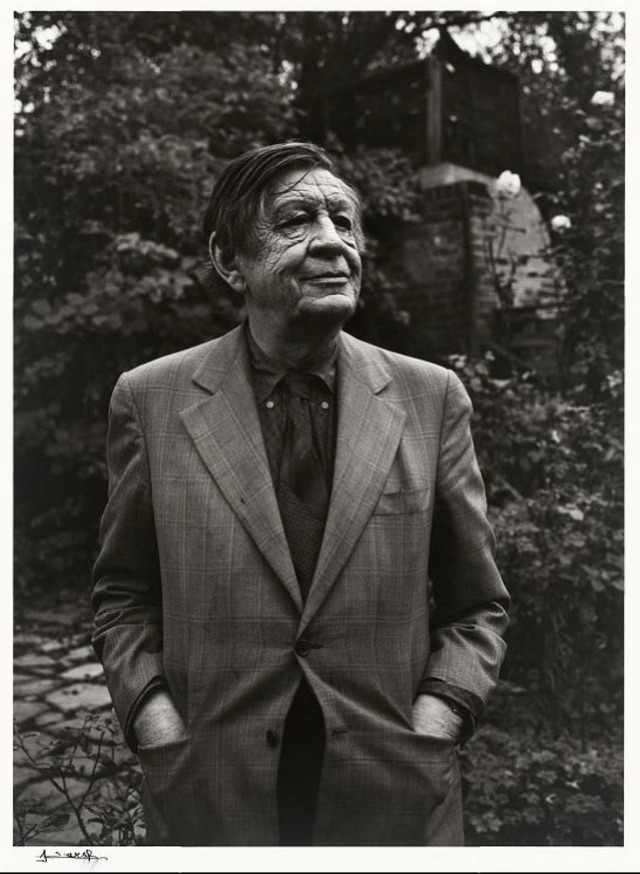

Yousuf Karsh, W. H. Auden, 1972. Gelatin silver print, Image: 27.9 x 20.4 cm (11 x 8 1/16″). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Estrellita Karsh in memory of Yousuf Karsh. © Estate of Yousuf Karsh. Digital Public Library of America.

W. H. Auden Response to Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

The students will now be asked to study Auden’s response to the same painting:

Musee des Beaux Arts

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

What are the major differences in form and content, between Williams and Auden? Auden prefers longer lines of verse, a clear use of end rhyme, a more conversational and instructive tone—as if he were giving a college lecture.

What adjective might describe the poem’s first line? Auden does not begin with description or emotion or an expression of self. His style might be characterized as axiomatic, didactic, or proverbial. Auden likes to offer pieces of wisdom about the human condition, in particular, the nature of human suffering—one of his favorite subjects. Usually Auden discusses suffering in the context of wars that he has witnessed. Here he sees the nature of suffering displayed in a painting.

Having sampled Sexton, Williams, and Auden, the students will hopefully understand that ekphrastic writing can take many forms—emotive, descriptive, and axiomatic being only a few examples. The students should now be able to take their knowledge and apply it to a larger assignment that involves the Washington and Lee collection.

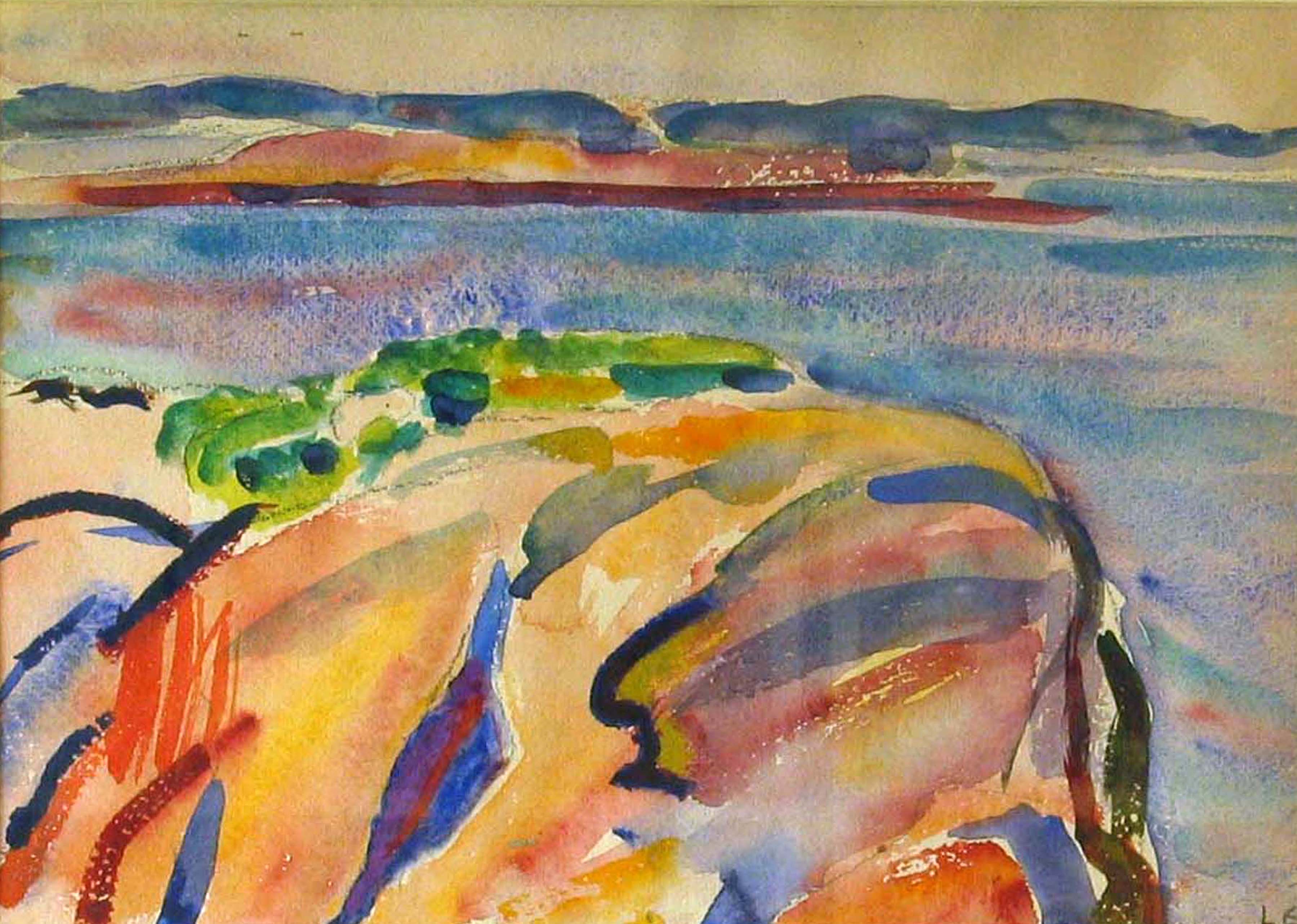

DAY THREE

We will meet at the Gottwald Gallery, where a UCAH staff member (often Pat Hobbs) will give the class a fifteen minute talk, introducing them to Louise Herreshoff’s life and paintings. The students will spend the rest of the class period choosing one work from the gallery that will be the centerpiece for their larger assignment: to write three separate ekphrastic poems about one painting in the galley. One poem must be in the style of Sexton, another in the style of Williams, and the third in the style of Auden. In other words the students must write a confessional poem in loose free verse, a minimalist, descriptive poem that has a central message, and a proverbial poem with the voice of a mild lecture, that contains some rhyming pattern.

The students will have two weeks to work on these poems, and will be given a reading list of other poems by Sexton, Williams, and Auden in order to immerse themselves in each poet’s style, and to begin to get the sound of each poet into their ears. The first visit to the Gottwald gallery provides an opportunity for each student to find a work of art that might inspire an emotional response, but that also contains a moral lesson that the students can capture in poetry. Repeated visits to the Gottwald gallery will be necessary on their own time in order to continue studying their chosen painting. The students should get to know the work intimately, to see what new responses it inspires over time. Images of most of these paintings are not available online—and internet images are no substitute for direct engagement with the work.

FINAL EVENT:

An Intimate Reading at the Gallery

On a chosen date, weeks later, the class will convene at the Gottwald gallery for a reading with invited guests. Each student will stand beside their chosen painting, give an introduction explaining why they chose this painting, what they see in it, and which of their poems they felt was most successful, before reading the poem, and taking any questions. Written copies of the students’ poems will be distributed in one packet for the audience to follow during the reading, and for the students and curators to keep.

This lesson was created by Laura Brodie, a novelist and visiting professor of English at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. This lesson can be used or adapted by other educators for educational purposes with attribution to Brodie. None of this material may be used for commercial purposes. Copyright of original artworks belongs to the artist and/or university. Please contact Andrea Lepage for information about the lesson or the Teaching with UCAH Project: lepagea@wlu.edu or (540) 458-8305. Toolkit Lesson “Ekphrastic Poetry—A Unit for a Creative Writing Seminar” by Laura Brodie is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.